II. BACKGROUND

According to American Cancer Society estimates, during 2013 there would be nearly 228,190 new cases of lung cancer. Lung cancer accounts for approximately 14 percent of all new cancers and it is the leading cause of cancer deaths, accounting for about 27 percent of all cancer deaths. Evaluation of new drugs for the treatment of lung cancer is based on well-conducted and controlled trials assessing appropriate endpoints to establish clinical benefit and support approval.

A. Endpoints Supporting Past Approvals

For regular approval of an NDA or BLA, the applicant must show direct evidence of clinical benefit or improvement in an established, validated surrogate for clinical benefit. FDA’s accelerated approval pathway,6 allows for the use of two additional types of endpoints to support approval of drugs or biological products that are intended to treat serious or life-threatening diseases and that provide a meaningful therapeutic benefit over existing treatments (e.g., demonstrate an improvement over available therapy or provide therapy where none exists).7 Specifically, accelerated approval may be based on: (1) an effect on a surrogate endpoint that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit; or (2) an effect on a clinical endpoint that can be measured earlier than irreversible morbidity or mortality and that is reasonably likely to predict an effect on irreversible morbidity or mortality or other clinical benefit.

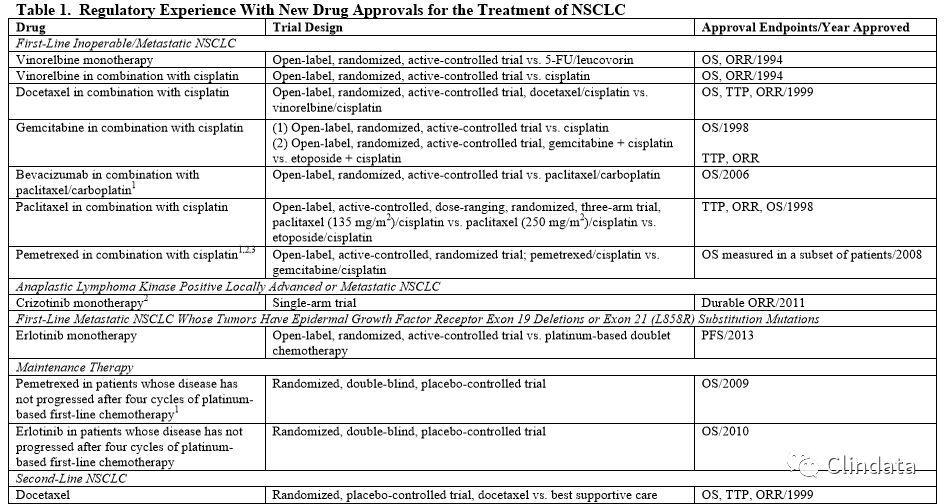

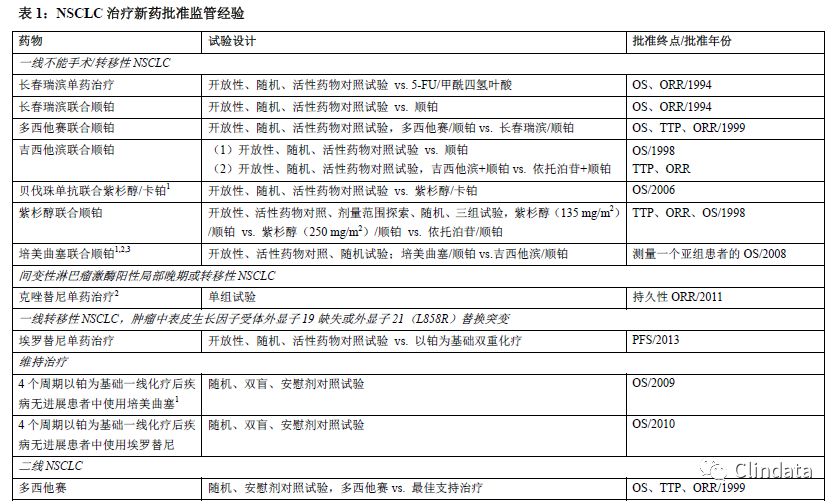

In the past, three commonly used efficacy endpoints in trials assessing treatments of lung cancer were overall survival (OS), time to progression (TTP) or progression-free survival (PFS), and objective tumor response rates (ORR) (see Table 1). Reduction in patients’ tumor-related symptoms has also been used as an efficacy endpoint (see Table 1). The majority of drug approvals for NSCLC have been based on a significant improvement in OS, as the median survival was relatively short (less than a year) and thus rarely increased the duration of the trial over use of PFS or ORR as a primary outcome measure. Additionally, OS is an optimal endpoint because the measurement is accurate, is observed on a daily basis, and provides direct evidence of clinical benefit to the patient. Regular approval was granted on the basis of a significant improvement in OS. Similarly, reduction in patients’ tumor-related symptoms can also provide direct evidence of clinical benefit and can support regular approval.

When the observed differences in TTP or PFS are of a substantial magnitude, then TTP or PFS may provide evidence of clinical benefit sufficient to support approval. The magnitude of the treatment effect is viewed in the context of the toxicity of the drug, the relatively short survival for NSCLC, especially in those with recurrent or treatment-refractory disease, available therapy for the stage, histologic or genetic subtype of NSCLC, and extent of prior treatment. Because of the significance of these individual factors, a fixed magnitude of effect that generally will support approval cannot be specified.

Treatment effects on ORR have not been demonstrated to reliably predict corresponding effects on survival in NSCLC. We consider demonstration of ORR alone to be a surrogate endpoint reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit only when the treatment effect size is large and the responses are durable. In these circumstances, ORR has been used as the basis only for accelerated approval for NSCLC. In other circumstances, such as when clinical trials have shown that ORR correlated with well-documented improvements in patient tumor-related symptoms (e.g., photodynamic therapy for treatment of obstructing endobronchial therapy), ORR has supported regular approval.

The criteria for disease progression and tumor response are based on subjective interpretation of radiographic images and clinical evaluation. These subjective interpretations have potential to introduce bias, particularly when evaluated in open-label trials. Specifically, primary lung tumors and regional nodal disease frequently have ill-defined borders that can be difficult to accurately and reproducibly measure radiographically. Therefore, confidence in tumor measurement-based outcomes depends on the frequency of assessments as well as clear, objective criteria for defining disease progression and tumor response. Substantial numbers of missing tumor assessments can potentially overestimate or underestimate treatment differences.

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures of tumor-related symptoms and functioning can provide direct evidence of treatment benefit if demonstrated to be well-defined and reliable assessments of a clinically meaningful concept or set of concepts, and if evaluated in wellconducted, placebo-controlled or double-blinded, randomized trials.10 Well-defined and reliable assessments include those that have documented evidence of content validity, construct validity, reliability, and ability to detect change, in addition to established methods for interpreting trial results.11 Well-conducted clinical trials include protocols with defined schedules for PRO assessment at frequencies that correspond to the intended claims, plans to minimize unintentional unblinding, and prespecified statistical strategies for handling missing data, particularly at or near the time of disease progression.

II背景

按照美国癌症协会的估计,2013年将有近228,190例肺癌新增病例。肺癌约占所有新发癌症病例的14%,而且是癌症死亡的主要原因,约占所有癌症死亡的27%。肺癌治疗新药评价基于规范实施的对照试验进行,评价适合的试验终点,以确立临床获益和支持批准。

A. 支持过去批准的终点

为获得NDA或BLA的常规批准,申请人必须提供直接证据证明有临床获益或临床获益有效指标有改善。FDA加快审批途径中允许使用两类新增终点,以支持批准用于治疗严重或危及生命疾病的药物或生物制品,也可支持批准治疗获益优于现有治疗的药物或生物制品(例如证明优于现有治疗或提供全新治疗)。具体来说,可基于下列情况进行加快审批:(1)对可合理预测临床获益的替代终点的影响;或(2)对不可逆发病或死亡之前可测量临床终点的影响,和对可合理预测对不可逆发病或死亡或其它临床获益影响的临床终点的影响。

过去,肺癌治疗临床评价试验中常使用总生存率(OS)、疾病进展时间(TTP)或无进展生存期(PFS)、客观肿瘤缓解率(ORR)3个疗效终点(参见表1)。也可将患者肿瘤相关症状减少用作疗效终点(参见表1)。大多数NSCLC药物的批准基于OS的显著改善,中位生存期相对较短(不到一年),因此与使用PFS或ORR作为主要终点指标相比,使用OS指标的试验很少需要延长试验时间。此外,OS测量准确,可每天观察,且能提供直接证据证明患者临床获益,因此,OS是最佳终点。基于OS的显著改善获得常规批准。同样,患者肿瘤相关症状减少也可作为临床获益的直接证据,且可支持常规批准。

当TTP或PFS实测结果差异非常大时,TTP或PFS可以提供足够多的临床获益证据支持药物批准。根据药物毒性、相对较短的NSCLC生存期(特别是复发或难治性疾病)、该阶段可用治疗、NSCLC组织学或基因亚型以及既往治疗程度判定治疗疗效。由于上述每个因素均非常重要,通常无法规定上述因素在支持药物批准中发挥的固定作用的程度。尚未证明药物对ORR的治疗作用能可靠预测对NSCLC生存期的作用。我们认为只有治疗作用明显且肿瘤缓解持久时,可证明ORR单独作为替代终点可合理预测临床获益。在上述情况下,ORR只用作NSCLC加快审批的基础。在其他情况下,例如临床试验显示ORR与有充分证据证明的患者肿瘤相关症状改善(例如用于阻塞性支气管治疗的光动力治疗)相关,ORR支持常规批准。疾病进展和肿瘤缓解标准基于对放射学和临床评价的主观解释确定。主观解释可能引入偏倚,尤其是在开放试验中评价时。具体来说,原发性肺部肿瘤和局部结节病的界限通常不明确,难以通过放射学准确重复测量。因此,肿瘤测量结果的可信度取决于评估频率以及明确、客观的疾病进展和肿瘤缓解判定标准。大量肿瘤评估缺失可能会高估或低估治疗差异。

如果证明有临床意义概念或一组概念的评估明确且可靠,而且是在规范实施、安慰剂对照或双盲、随机试验中进行评价,则患者报告结果(PRO)指标肿瘤相关症状和功能可提供治疗获益的直接证据。除了用于解释试验结果的确定方法之外,明确可靠的评估包括有证据记录了内容有效性、结构有效性、可靠性和检测变化能力的评估。

10参见“肿瘤药物咨询委员会癌症临床试验和肺癌临床试验终点”副本(2003年12月16日,pp 188-368)(http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/03/transcripts/4009T1.pdf)。11参见“患者报告结果指标:在医疗产品研发中使用以支持标签声明”行业指导原则。规范实施的临床试验包括按照PRO评估频率预期要求确定的试验方案、最小化意外揭盲计划以及处理缺失数据的规定统计策略,尤其是处于或接近疾病进展时。

B. Summary of Workshop and Advisory Committee Discussions

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the FDA held a public workshop on lung cancer endpoints on April 15, 2003, with participants that included representatives from the FDA, ASCO, the National Cancer Institute, academia, advocacy groups, and industry.12 The workshop primarily addressed advanced and metastatic NSCLC, and participants discussed the pros and cons of using OS, tumor assessment-based endpoints, and PRO measures in evaluating drugs for marketing approval. These discussions recognized that although ORR is a commonly used endpoint, it does not predict effects on OS. The clinical significance of small differences in TTP may be unclear, especially when evaluating toxic therapy. TTP is subject to ascertainment bias in open-label trials, and bias can occur if follow-up schedules are asymmetric among trial arms.

Speakers at the workshop noted that assessment of disease progression at frequent intervals is labor intensive and can be expensive. PRO measures can constitute important clinical benefit endpoints, particularly in a predominantly symptomatic disease such as NSCLC. However, adequate evaluation of treatment effect based on PRO measures involves blinded, randomized trials using instruments that reliably and validly measure concepts that define treatment benefit in the targeted clinical trial population, with response options and a recall period that have been demonstrated to be appropriate and interpretable in the subset of patients studied. Analytical challenges, including sensitive but uninterpretable instruments or large amounts of missing data, pose additional difficulties in evaluating an experimental therapy based on PRO data. OS is considered the most appropriate endpoint that is definitive and easy to determine. An observed OS benefit in a well-conducted, randomized trial can be directly attributed to the experimental therapy.

Subsequent to the above-mentioned public workshop, an ODAC meeting was held on December 16, 2003, in which the workshop discussions regarding lung cancer endpoints were presented to the committee.

(1) The committee voted 17 to 2 that since no drug was approved for the adjuvant treatment of NSCLC, hypothetically disease-free survival can be a reasonable endpoint to evaluate new therapy in an adjuvant setting.

(2) As of the date of the meeting, approval for the treatment of metastatic NSCLC generally had been based on demonstration of improvement in OS. The committee considered whether studies incorporating a tumor-based time-to-event endpoint such as PFS or TTP as a primary endpoint could support regular approval, or only accelerated approval. The committee recommended that the tumor-based endpoint of PFS be considered to be preferable to TTP, since PFS includes deaths particularly when there are missing assessments. The uncertainties in measuring PFS were recognized (e.g., measure provides indirect evidence of clinical benefit, unclear clinical meaning of small differences in PFS, the noise and variability in the assessments caused by imaging or timing of assessments, missing and unevaluable data). The committee voted 11 to 8 that PFS may be used as an endpoint to evaluate drug effect in metastatic disease for consideration of regular approval.

(3) Regarding the evaluation of drug effect in inoperable or locally advanced disease, the committee voted 15 to 3 that an effect on PFS should not be considered sufficient to support regular approval and that new drugs should be evaluated based on OS. To consider differences in PFS as the basis for accelerated approval, the committee was of the opinion that the treatment differences based on PFS had to be substantial (e.g., 3 months or more). It was also recognized that PRO endpoints, such as delay in symptom progression, are important and that better tools are needed to minimize bias and to define what constitutes a benefit.

(4) The committee also discussed the challenges in using noninferiority trial designs with OS and PFS endpoints. A trial with a noninferiority hypothesis should be considered only if the active control has established efficacy, the active control effect size can be estimated for patients with the indication under consideration, and the percent of active control effect size to be retained can be prespecified.13 The effect size of the active control on the primary endpoint of interest should be established based on meta-analysis of historical, randomized trials. It is not possible to prespecify the percent of active control effect size to be retained when the active control effect size is not well established. When considering trials with a noninferiority hypothesis, an assumption that should be assessed is the constancy of the treatment effect over time attributed to the active comparator. Because medical practice, clinical trial conduct, the timing of tumor progression assessments, the radiological modalities used, and the criteria and definition for assessing progression that have evolved over time vary between trials, especially when trials are conducted in different geographic regions, it is difficult to verify the constancy assumption with PFS as primary endpoint.

Based on these recommendations from the 2003 advisory committee meeting, we have continued to recommend OS as the primary endpoint for NSCLC clinical trials. However, a clinical trial demonstrating a large improvement in PFS, with acceptable toxicity, could potentially lead to regular approval, particularly in an unmet medical need population.

B. 研讨会和咨询委员会讨论总结

2003年4月15日,美国临床肿瘤学会(ASCO)与FDA举行了一次关于肺癌终点的公开研讨会,参与者包括FDA、ASCO、美国国家癌症研究所、学术界、利益相关团体以及行业代表。

(1) 委员会投票结果为17:2,赞成下列结论:由于没有药物批准用于NSCLC辅助治疗,假定无疾病生存期可在辅助治疗背景下作为合理终点评估新治疗方法。研讨会主要关注晚期和转移性NSCLC,参会人员讨论了在药品上市许可评估中使用OS、基于肿瘤评估的终点以及PRO指标的利弊。讨论发现虽然ORR是常用终点,但是不能预测治疗对OS的影响。可能不清楚TTP较小差异的临床意义,特别是在评估有毒治疗时。TTP在开放性临床试验中易发现偏倚,而且如果各试验组中随访计划不对称,则可能发生偏倚。研讨会发言者指出,频繁评估疾病进展需要密集劳动,且费用较高。PRO指标可以构建重要的临床获益终点,尤其是在主要症状疾病中,例如NSCLC。然而,只有盲态、随机临床试验在临床试验目标人群中采用可靠有效测量工具测量治疗获益概念,且在研究患者亚组中已经证明缓解选项和回忆期的适用性和合理性时,方可根据PRO指标充分评估治疗作用。分析挑战包括敏感度但是无法解释的工具或大量缺失数据,对基于PRO数据评估试验治疗带来更多的困难。由于OS明确且容易测定,因此认为OS是最适合的终点。在规范实施的随机试验中,OS获益的实测结果可以直接归因于试验治疗。继上述公开研讨会之后,2003年12月16日举行了ODAC会议,向委员会报告了肺癌终点研讨会的讨论内容。

(2) 截至会议日期,通常基于OS改善结果批准转移性NSCLC治疗。委员会考虑研究是否可以加入一个基于肿瘤的到事件发生时间终点(例如PFS或TTP)作为主要终点,以支持常规批准或只是支持加快审批。委员会建议,因为PFS包括死亡,基于肿瘤的PFS终点较TTP更为可取,尤其在有缺失评估时。公认测量PFS时有不确定性,例如指标提供了临床获益的间接证据,PFS差异较小时临床意义不明确,在评估中由于影像学或评估时间导至噪音和变异性,有缺失和无法评价的数据。委员会投票结果为11:8,认为在常规批准时,PFS可作为终点评估药物在转移性疾病中的作用。(3) 委员会投票15:3认为,评价不能手术或者局部晚期疾病药物的作用时,药物对PFS的作用不足以支持常规批准,而应基于OS评价新药。考虑到加快审批基础PFS的差异,委员会认为基于PFS的治疗差异必须足够大(例如3个月或者以上)。委员会还认识到PRO终点(例如症状进展延迟)非常重要,且需要更好的工具减少偏倚和确定获益构成要素。

(4) 委员会还讨论了使用非劣效性试验设计以及OS和PFS作为终点的挑战。只有在已确定活性对照药物的疗效,可以估计该药物对患者考察适应症的活性对照效应量,且可以提前规定活性对照效应量的保持百分比,才可考虑非劣效性假设试验。

III. 建议应当基于历史、随机试验的荟萃分析,确定活性对照药物对主要终点的效应量。尚未完全确定活性对照效应量时,不可能提前规定活性对照效应量的保留百分比。考虑采用有非劣效性假设的临床试验时,应当评估假设内容,即随时间推移,活性对照药物治疗作用恒定。由于各项试验中医学实践、临床试验实施、肿瘤进展评估时间、所用放射学检查形式以及进展评估标准和定义随时间推移有不同变化,尤其是在不同地区实施的试验,PFS作为主要终点难以证实恒定假设。基于2003年咨询委员会会议的上述建议,我们继续推荐OS作为NSCLC临床试验的主要终点。然而,若临床试验证明PFS有较大改善,且药物毒性可接受,可能会获得常规批准,尤其是针对医学需求未得到满足的人群。

III. RECOMMENDATIONS

We consider OS to be the standard clinical benefit endpoint that should be used to establish efficacy of a treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC. However, other endpoints can be considered for regulatory decision-making based on the population and riskbenefit profile of a drug. We also recognize that it may not always be feasible to conduct separate trials in patients with locally advanced and metastatic NSCLC.

PFS may be appropriate as the primary endpoint to establish efficacy for drug approval if the trial is designed to demonstrate a large magnitude for the treatment effect as measured by both the hazard ratio and absolute difference in median PFS and an acceptable risk-benefit profile of the drug is demonstrated. Sponsors should justify use of PFS as the primary efficacy endpoint and the magnitude of PFS effect considered likely to predict OS or to represent clinical benefit versus the risk of the drug in the context of the lung cancer stage and results of treatment with alternative therapy. Because of the subjectivity in the measurement of PFS assessments and the fact that the assessments depend on frequency, accuracy, reproducibility, and completeness, the observed magnitude of effect should be substantial and statistically robust. If investigatorassessed PFS is considered the primary endpoint for establishing efficacy, then evidence of lack of bias should be provided, for example, by verification of investigator assessment in a random sample audit conducted by an independent review committee.

Planned interim efficacy analyses based on OS may be appropriate. However, interim efficacy analyses of PFS before completion of patient accrual are discouraged. Early interim efficacy analyses of PFS that cross a stopping boundary often overstate the magnitude of the effect. An interim PFS efficacy analysis is unlikely to provide an accurate or reproducible estimate of the treatment effect size because of inadequate follow-up, missing assessments, inconsistent readings between radiological reviewers, and/or lack of concordance between investigators and independent assessors. Stopping a trial based on interim PFS efficacy results that may not be verifiable after adjudication can render the trial results uninterpretable. In addition, a statistically significant difference in PFS that is small in magnitude may not be deemed clinically meaningful. Interim analyses to detect harmful effects or futility for PFS or OS endpoints may be appropriate.

We encourage the development of well-defined and reliable PRO instruments that capture the essential treatment benefit concepts in the targeted population. To interpret PRO data, it is generally useful to gather a complete record of all doses of the concomitant medications, such as analgesics, antidepressants, antiemetics, and antidiarrheals, that may confound interpretation of the PRO of interest and limit the ability to differentiate anticancer treatment effects from the effects of concomitant medication. Recording of concomitant medications can be accomplished using PRO instruments (i.e., event logs) or other assessment tools. We will review the adequacy of all PRO measures based on the principles outlined in the guidance for industry PatientReported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims.

Regardless of which efficacy endpoints are chosen, NSCLC is a heterogeneous disease with varying response to treatment across different molecular and histopathologic subgroups (e.g., pemetrexed, erlotinib). We recommend that clinical trials be prospectively designed to evaluate such differences in treatment effect.14

Although general principles outlined in this guidance should help applicants select endpoints for marketing applications, we recommend that applicants meet with the FDA before submitting protocols intended to support NDA or BLA marketing applications. These meetings will include a multidisciplinary FDA team of oncologists, statisticians, clinical pharmacologists, measurement experts, and often external expert consultants. Applicants can also submit a request for special protocol assessment to obtain confirmation of the appropriateness of endpoint measures and protocol design for individual trials, considered within the context of the overall development program, intended to support drug marketing applications.15 Marketing approval depends not only on the design of clinical trials, but on FDA review of the results and data from all trials in the marketing application. Applicants who plan to prospectively evaluate treatment effects in a defined subgroup of NSCLC (e.g., a molecularly defined subgroup) should identify such a development program early and refer to guidance on co-development of drugs and devices in the guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff In Vitro Companion Diagnostic Devices.

III建议

我们认为OS作为标准临床获益终点,应当用于在局部晚期或转移性NSCLC患者中确定治疗疗效。然而,基于人群和药物风险获益特征,药政机构作出决定时可以考虑其他终点。我们还认识到并非始终可以在局部晚期或转移性NSCLC患者中实施独立试验。

如果临床试验旨在证明通过风险比以及中位PFS绝对差异可测量较大程度的治疗效应,而且已证明药物风险获益特征可接受,则PFS可作为主要终点确定药物疗效以供药物审批使用。申办方应当证明使用PFS(作为主要疗效终点)和PFS效应程度可以预测OS,或可代表药物在不同肺癌阶段时的获益风险特征及替代治疗结果。由于PFS评估测量时存在主观性,以及评估依赖于频率、准确、重现性和完整性的事实,观测到的效应程度应当较大而且具有统计学稳健性。如果将研究者评估的PFS作为主要终点用于确定疗效,则应当提供证据证明评估中无偏倚,例如在由独立评审委员会实施的随机样本审核中证明研究者评估无偏倚。可基于OS进行计划中期疗效分析。然而,不鼓励在患者获益完成之前进行中期疗效分析。早期PFS中期疗效分析与终止边界交叉,通常夸大效应程度。由于随访不足、评估缺失、不同放射学阅读者读取结果不一致和/或研究者与独立评估者之间缺乏一致性,中期PFS疗效分析不太可能提供准确或可重复的治疗作用程度估计结果。根据中期PFS疗效结果终止试验后,可能无法证实该判断是否使试验结果无法解释。此外,认为较小程度的有统计学意义的PFS差异没有临床意义。期中分析可检测PFS或OS终点有害作用或无用性。我们鼓励开发明确可靠的PRO测量工具,其可在目标人群中捕捉基本治疗获益概念。解释PRO数据时,通常需要收集联用药物(例如镇痛药、抗抑郁药、止吐药、止泻药)所有用药剂量的完整记录,其可能会混淆对PRO关注结果的解释,以及限制区分抗癌治疗效应与联用药物效应的能力。可以采用PRO工具(例如事件日志)或其他评估工具记录联用药物。我们将按照“患者报告结果指标:在医疗产品研发中使用以支持标签声明”行业指导原则中概述的原则审查所有PRO指标的适用性。

无论选择何种疗效终点,由于NSCLC是一种异质性疾病,因此对于不同分子及组织病理学亚组(例如培美曲赛,埃罗替尼)治疗的缓解不同。我们建议采用前瞻性设计临床试验来评价治疗作用差异。

虽然本指导原则中概述的一般原则应当有助于申请人选择上市申请的终点,但是我们建议申请人在提交支持NDA或BLA上市申请的方案之前应与FDA开会沟通。与会人员将包括肿瘤学家、统计学家、临床药理学家、测量专家组成的多学科FDA团队,且常包括外部专家顾问。申请人还可以提交特殊试验方案评估请求,以获得整体研发项目各项试验的终点指标和试验方案的适用性证明,预期支持药物上市申请。上市批准不仅取决于临床试验的试验设计,而且取决于FDA对上市申请中所有试验结果和数据的审查。若申请人计划在确定的NSCLC亚组中(例如分子亚组)前瞻性评价治疗作用,应当在早期确定这样的开发项目,并依照行业指导原则中药物和器械联合研发指导原则和美国食品和药品监督管理局工作人员“体外伴随诊断装置”指导原则进行。

APPENDIX A: TUMOR MEASUREMENT DATA COLLECTION16

The following are important considerations for tumor measurement data. We recommend that:

The case report form (CRF) and electronic data document the target lesions identified during the baseline visit before treatment. The possibility of bias cannot be eliminated when retrospective identification of lesions is made for local site evaluations of tumor-based endpoints.

Tumor lesions be assigned a unique identifying letter or number. This assignment differentiates among multiple tumors occurring at one anatomic site and matches tumors measured at baseline with tumors measured during follow-up.

A mechanism be in place that ensures complete data collection at critical times during follow-up. The CRF should ensure that all target lesions are assessed at baseline and that the same imaging or measuring method is used for all tests required at baseline and follow-up.

The CRF contains data fields that indicate whether scans were performed at each visit.

A zero be recorded when a lesion has completely resolved. Otherwise, disappearance of a lesion cannot be differentiated from a missing value.

Follow-up tests provide for timely detection of new lesions both at initial and at new sites of disease. The occurrence and location of new lesions should be recorded in the CRF and in the submitted electronic data for both protocol-specified evaluations and those identified on unscheduled visits.

附录A:肿瘤测量数据采集

下文是针对肿瘤测量数据需要考虑的重要事项。我们建议:

● 在治疗前基线访视期间,在病例报告表(CRF)和电子数据中记录发现的目标病变。局部评估中采用基于肿瘤的终点对病变进行回顾性确认时,不能消除偏倚可能性。

● 为肿瘤病变分配特有的标记字母或数字。这种分配方法能够区分在一个解剖部位发生的多个肿瘤,并能将在基线测量的肿瘤与在随访期间测量的肿瘤匹配。

● 适合的机制可确保在随访期间关键时期可采集完整数据。CRF应当确保在基线时评估了所有目标病变,且在基线和随访要求进行的所有检测中使用相同的影像学或者测量方法。

● CRF描述了每次访视是否进行扫描。

● 当病变已完全缓解时记录为零。否则,无法区分病变消失与缺失值。

● 随访检测可及时发现在最初部位及新疾病部位出现的新病变。对于方案规定评估及非计划访视中发现的病变,均应当在CRF和提交的电子数据中记录新病变的发生和位置。

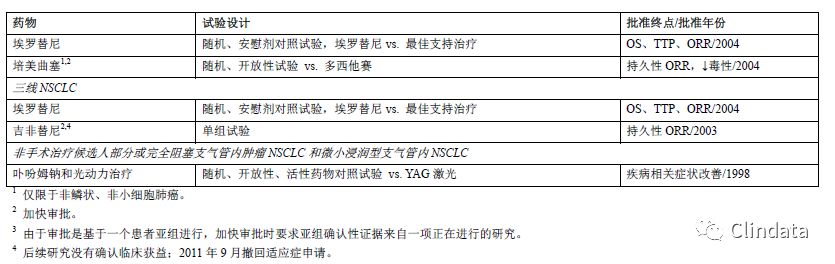

APPENDIX B: ISSUES TO CONSIDER IN PFS ANALYSIS

The protocol and statistical analysis plan (SAP) should detail the primary analysis of PFS. This analysis should include a detailed description of the endpoint, appropriate modalities for evaluating tumors, and procedures for minimizing bias. One or two secondary analyses should be specified to evaluate anticipated problems in trial conduct and to assess whether results are robust. The following important factors should be considered.

Definition of progression date. In survival analyses, the exact death date is known. In PFS analyses, the exact progression date is unknown. The following two methods can be used for defining the recorded progression date (PDate) used for PFS analysis.

1. PDate assigned to the first time at which progression can be declared.

For progression based on a new lesion, the PDate is the date of the first observation that the new lesion was detected.

If multiple assessments based on the sum of target lesion measurements are done at different times, the PDate is the date of the first observation or radiological assessment of target lesions that shows a predefined increase in the sum of the target lesion measurements.

2. PDate as the date of the protocol-scheduled clinic visit immediately after all radiological assessments (which collectively document progression) have been done. Generally, this is recommended for sensitivity analysis.

Definition of censoring date. Censoring dates are defined in patients with no documented progression before data cutoff or dropout. In these patients, the censoring date is often defined as the last date on which progression status was adequately assessed. One acceptable approach uses the date of the last assessment performed. However, multiple radiological tests can be evaluated in the determination of progression. A second acceptable approach uses the date of the clinic visit corresponding to these radiological assessments.

Definition of an adequate PFS evaluation. In patients with no evidence of progression, censoring for PFS often relies on the date of the last adequate tumor assessment. A careful definition of what constitutes an adequate tumor assessment includes adequacy of target lesion assessments and adequacy of radiological tests both to evaluate nontarget lesions and to search for new lesions.

Analysis of partially missing tumor data. Analysis plans should describe the method for calculating progression status when data are partially missing from adequate tumor assessment visits.

Completely missing tumor data. Assessment visits where no data are collected are sometimes followed by death or by assessment visits showing progression. In other cases, the subsequent assessment shows no progression. In the latter case, it may seem appropriate to continue the treatment and continue monitoring for progression. However, this approach treats missing data differently depending upon subsequent events and can represent informative censoring when progression or death is recorded subsequently. Another possible approach is to include data from subsequent PFS assessments. This can be appropriate when evaluations are frequent and when only a single follow-up visit is missed. Censoring at the last adequate tumor assessment can be more appropriate when there are two or more missed visits.

The SAP should detail primary and secondary PFS analyses to evaluate the potential effect of missing data. Reasons for dropouts should be incorporated into procedures for determining censoring and progression status. For instance, for the primary analysis, patients going offstudy for undocumented clinical progression, change of cancer treatment, or decreasing performance status can be censored at the last adequate tumor assessment. The secondary sensitivity analysis would include these dropouts as progression events. Although missed visits for progression can be problematic, all efforts should be made to keep following patients for disease progression irrespective of the number of visits missed. Another analysis could ignore these missing assessments and consider the date that progression or death is recorded in a subsequent assessment as the time to event.

Progression of nonmeasurable disease. When appropriate, progression criteria should be described for each assessment modality (e.g., CT scan, bone scan).

Suspicious lesions. An algorithm should be provided for evaluating and following indeterminate lesions for assignment of progression status at the time of analysis.

附录B:在PFS分析中考虑的问题

方案和统计分析计划(SAP)应当详细描述PFS主要分析。此分析应当详细描述终点、评价肿瘤的适当方法以及减少偏倚的程序。应当规定一或两项次要分析,以评价试验实施中预期的问题,并评价这些结果是否有稳健。应当考虑下列重要的因素。

● 进展日期定义。在生存分析中,已知确切的死亡日期。在PFS分析中,确切的进展日期未知。可以使用下列两种方法定义PFS分析中所用的进展记录日期(PDate)。

1. 宣布出现进展时首次分配的PDate。

– 对于基于新病变的进展,PDate是指首次发现新病变的日期。

– 如果已经在不同时间基于目标病变测量结果总和进行了多重评估,则PDate是指首次发现目标病变或放射学评估显示目标病变测量结果总和增加(预先定义)的日期。

2. PDate是指在所有放射学评估之后立即进行方案计划临床访视的日期(共同记录进展)。通常建议对其进行敏感性分析。

● 删失日期定义。删失日期针对在数据截止或脱落之前没有记录进展的患者。在这些患者中,删失日期通常定义为最后一次充分评估进展状态的日期。也可使用末次评估日期。然而,在确定进展时可以评价多种放射学检测。另外,也可采用与这些放射学评估相对应的临床访视日期。

● PFS充分评估的定义。在没有进展证据的患者中,PFS删失通常取决于末次肿瘤充分评估的日期。构成肿瘤充分评估的仔细定义包括目标病变评估的充分性以及评估非目标病变以及寻找新病变时放射学检测的充分性。

● 部分缺失肿瘤数据分析。当肿瘤充分评估访视中缺失部分数据时,分析计划应当描述进展状态的计算方法。

● 完全缺失肿瘤数据。若评估访视中没有采集到数据,之后有时会出现死亡或评估访视显示疾病进展。在其他情况下,后续评估显示没有进展。在后一种情况中,可继续治疗或者继续监测进展。然而,这种方法根据后续事件情况对缺失数据进行不同处理,当在后续记录到进展或死亡时代表信息删失。另一种可能方法是包括后续PFS评估的数据,当频繁评估和只缺失一次随访访视时,可采用该方法。当有两次或者更多缺失访视时,在末次肿瘤充分评估时删失可能更为合适。

SAP应详细描述主要和次要PFS分析,以评价缺失数据的潜在影响。应将脱落原因纳入程序以确定审查和进展状态。例如,主要分析中,可在末次肿瘤充分评估时删失由于无事实证明临床进展退出研究、改变癌症治疗或体能状态降低的患者。次要敏感性分析将包括这些脱落,将其作为进展事件。虽然缺失进展访视可能有问题,但不论患者缺失几次访视,均应努力随访患者的疾病进展。另一种分析可忽略这些缺失评估,并考虑在后续评估中将进展或死亡记录日期作为事件发生时间。

● 不可测量疾病进展。如适用,应描述针对每种评估方式(例如CT扫描、骨骼扫描)的进展标准。

● 疑似病变。分析时应提供评价和随访不确定病变并分配进展状况的算法。

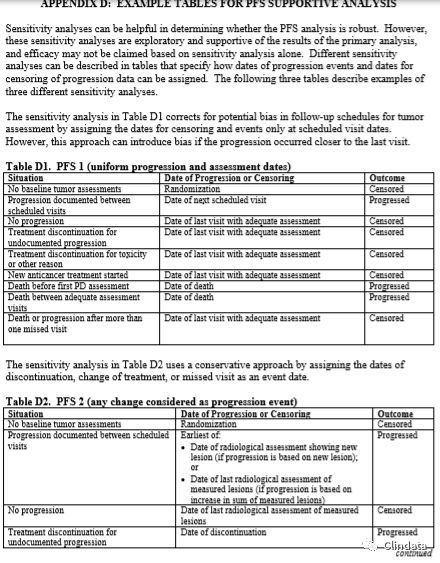

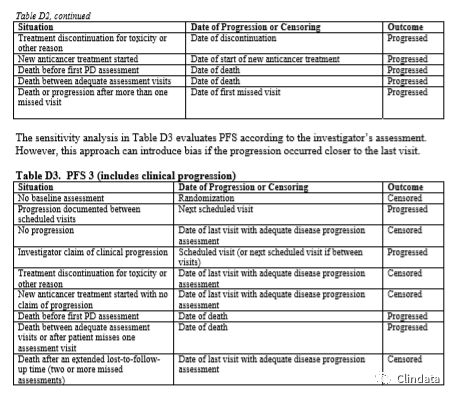

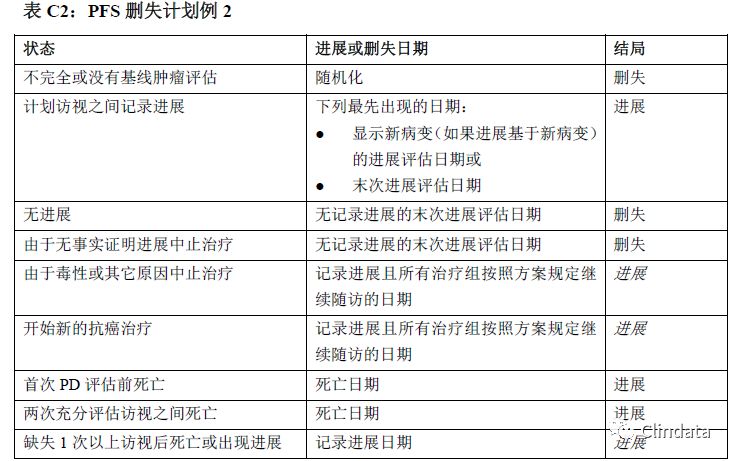

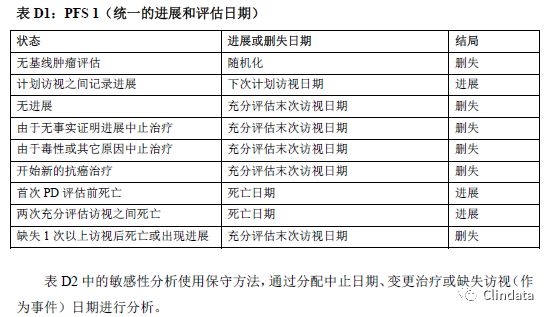

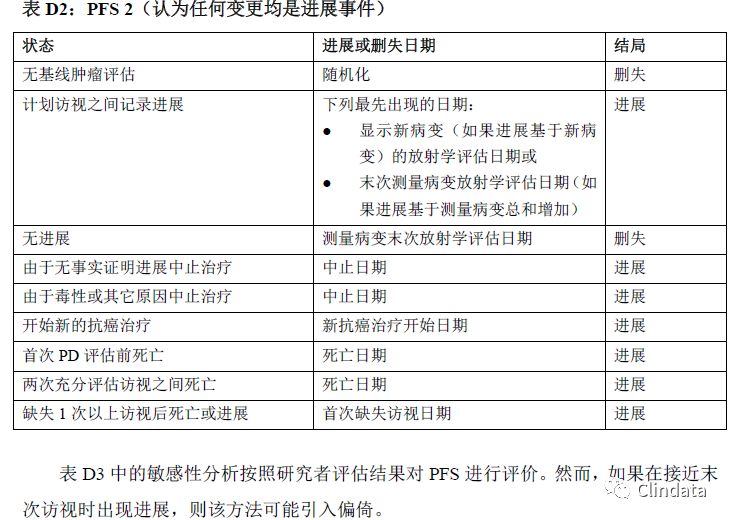

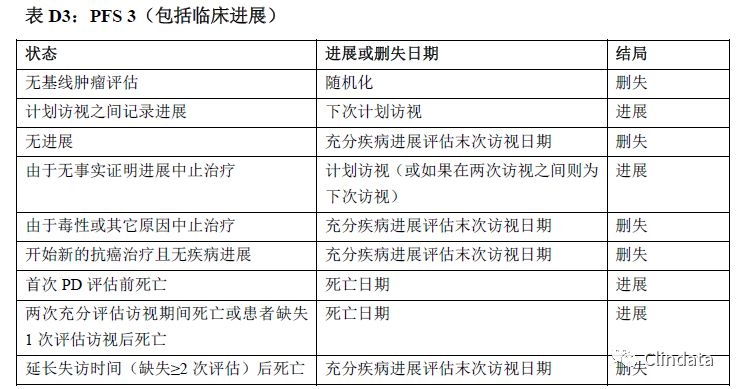

附录D:PFS支持性分析示例表

敏感性分析有助于确定PFS分析是否稳健。然而,这些敏感性分析是探索性分析,且支持主要分析结果,而且只根据敏感性分析可能无法确定疗效。表格中描述了不同的敏感性分析,规定如何分配进展事件日期和进展数据删失日期。下列三个表格描述了三种不同敏感性分析的示例。表D1中的敏感性分析通过分配审查日期和只在计划访视日期分析的事件校正肿瘤评估随访计划中的潜在偏倚。然而,如果在接近末次访视时出现进展,则该方法可能引入偏倚。

/3

/3